Gearman: Misunderstood wrangler of herds

For a few years now, I have maintained Gearman.

Upon taking over maintainership, I just wanted to get some bug fixes out the door, and revitalize the community which had grown stagnant after the former maintainers were unable to keep things up to date.

Since then we’ve shipped a few releases, updated for new compilers and kind of reached a stable place.

But one troubling trend I’ve seen is that folks don’t seem to use Gearman for what it’s actually good at. Many are using Gearman for what any messaging or queueing protocol can do.

See, the Gearman protocol was conceived of by the same folks that thought up the Memcache protocol. The similarities are quite obvious.

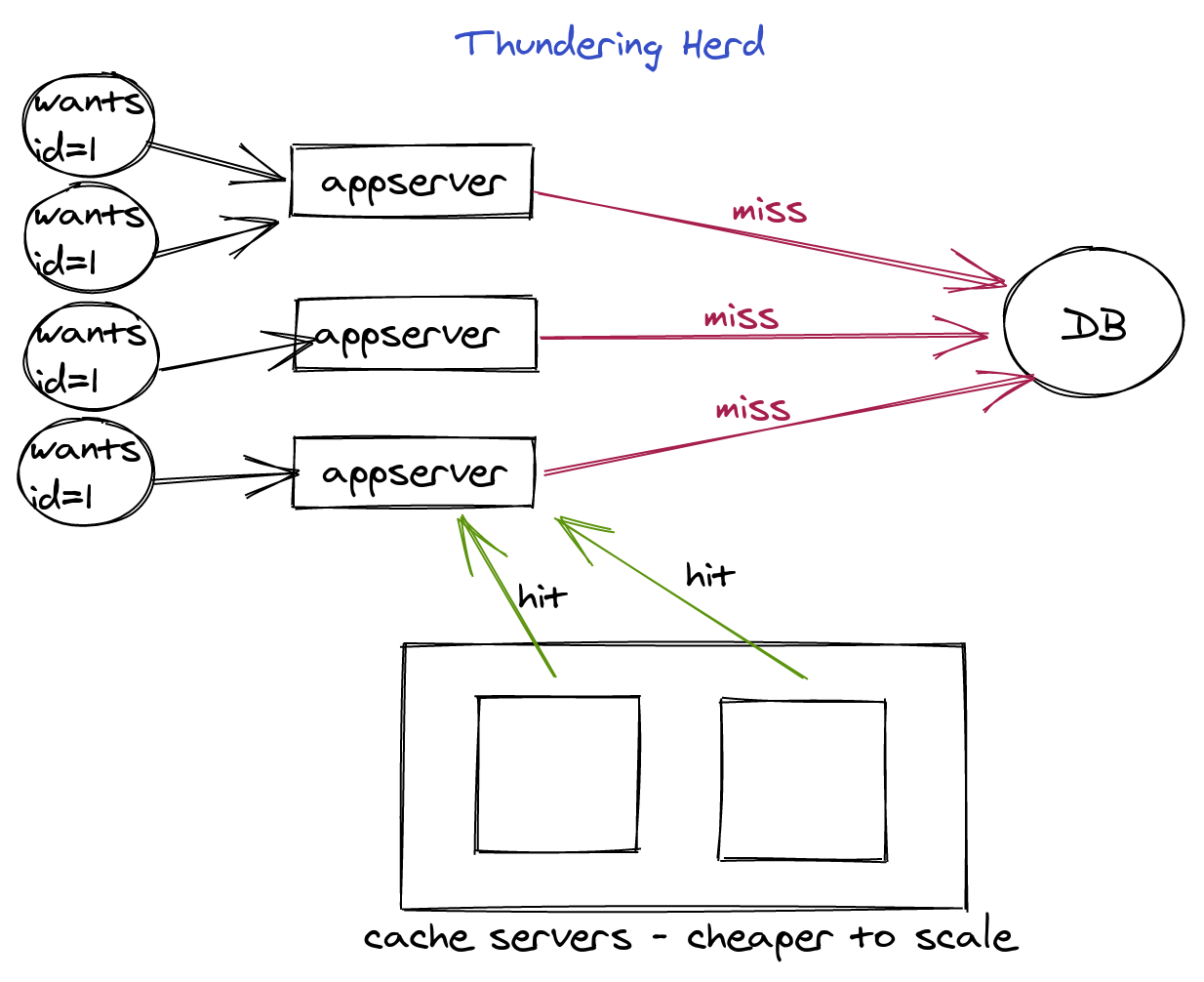

That’s no coincidence. The original design of memcached quickly met with a troubling problem: The Thundering Herd. This is the situation that occurs when one relies solely on caching to reduce expensive operations. Upon expiry, eviction, or genesis of a popular cache entry, you will have many requests for the result, and you must manage the number of expensive threads spawned as a result.

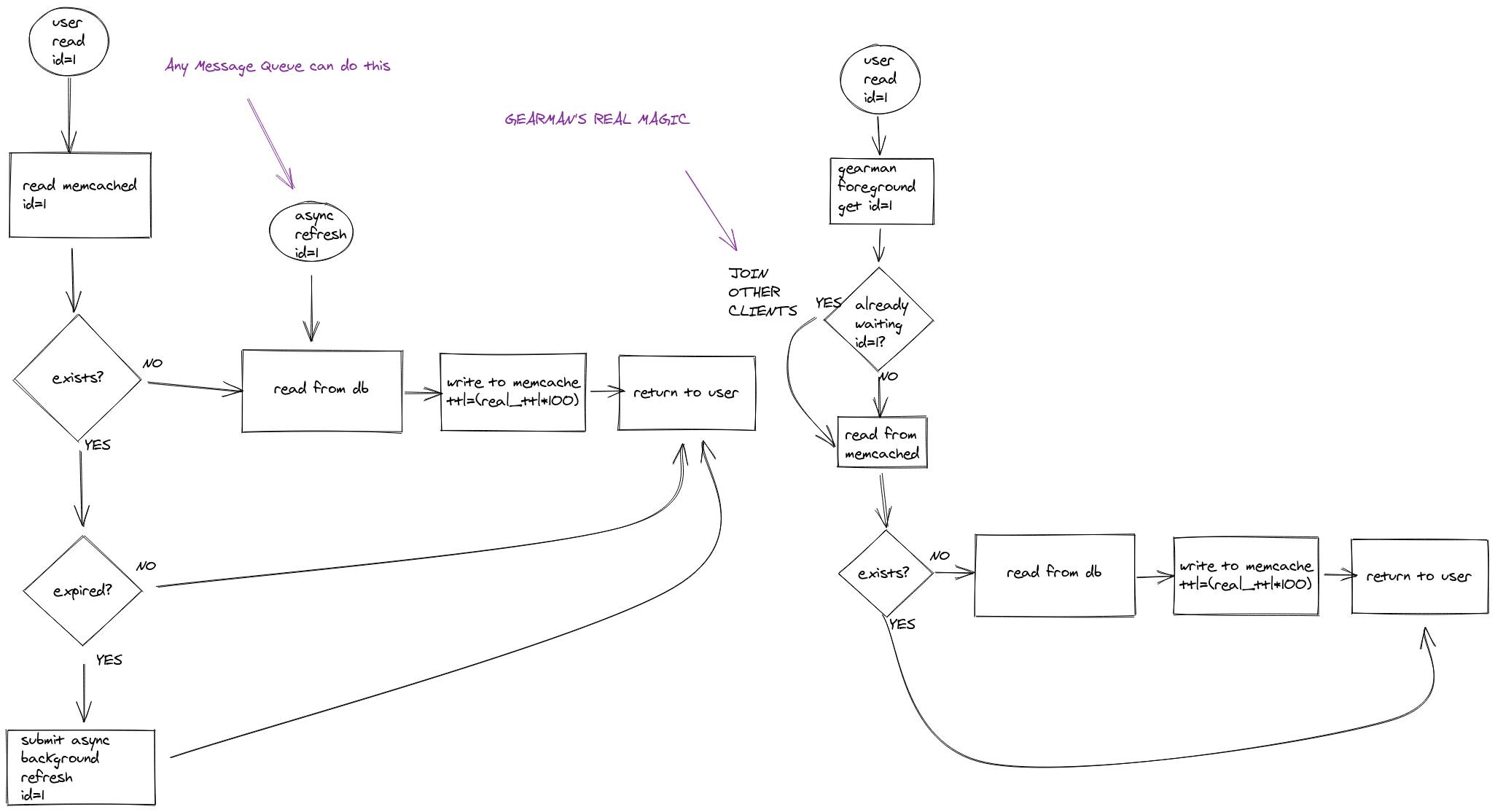

There are a few ways to solve this problem. The most common that you will find is “soft expiry”, you can see implementations such as turnstile and dogpile. This is where one stores a soft expiry time in the cache item. When your caching code sees a soft-expired item, it can spawn an async job to refresh, but still serve the old bit to the user. dogpile even implements a lock so that only one thread actually runs to regenerate. There are a few relatively simple ways to make this happen, and a job queue is only one of them.

This solves happy-path expiry pretty well, I’ve used it myself. However, it still has trouble with a bunch of normal things, like new-but-popular items, and loss of memcache servers. Basically, if you can’t find even a soft-expired entry in the cache, then every user has to wait while your requests run, and then they must re-read from cache, or somehow get the answer back from the job.

This isn’t so far-fetched. Memcached uses LRU expiry. This means that popular items stay in cache until their TTL, and less popular items are evicted when space is needed, even before their hard-expiry time. If you’re running memcached at full capacity, it should be evicting the least popular things. But if you have a very even distribution of popularity, you’ll be evicting things that are just moderately popular. Also, many systems will make a new entry popular immediately, thus needing a real way to coordinate the requests to it before it has even been cached in all the places it needs to be.

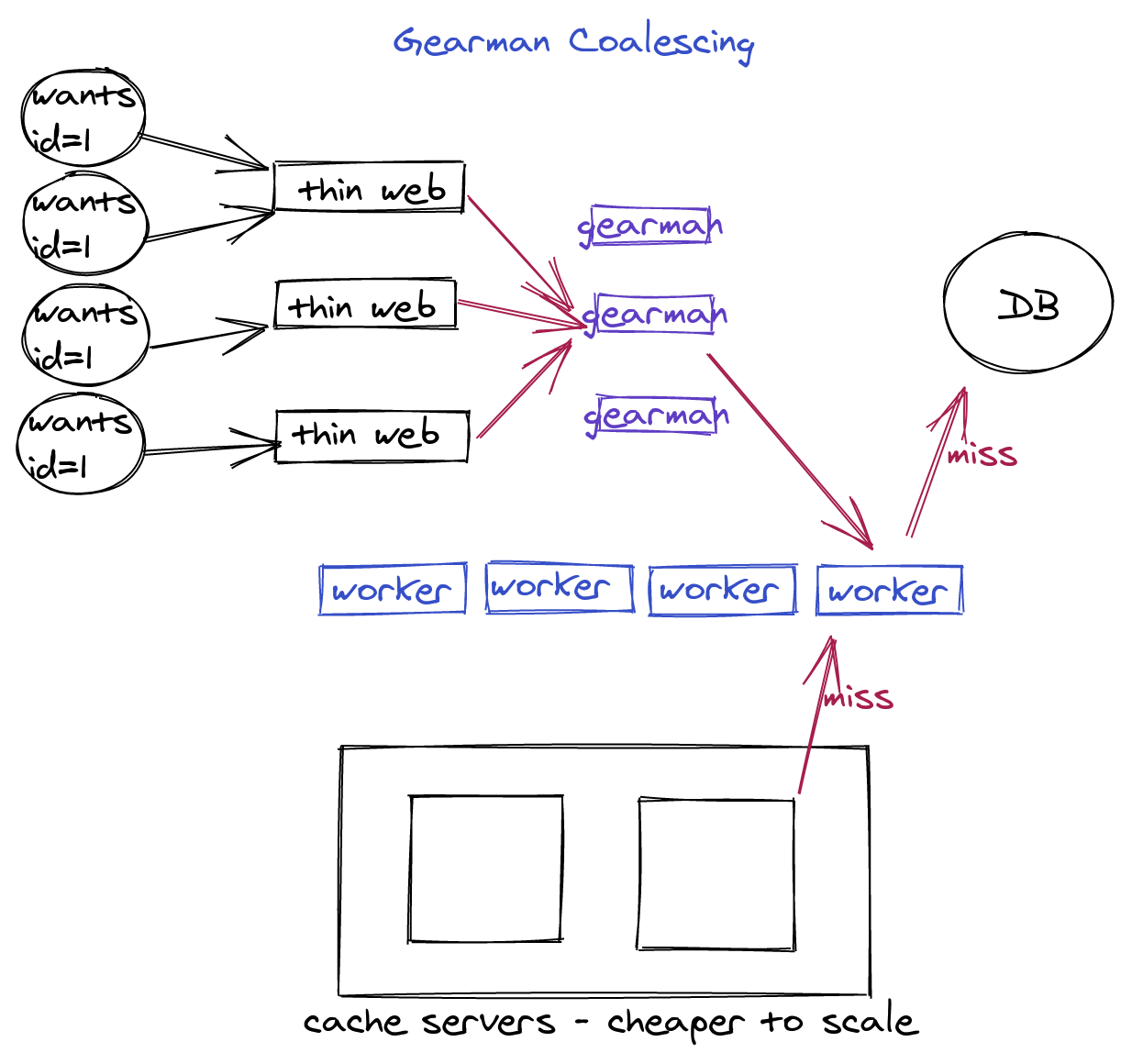

The gearman authors came up with a really cool solution for this, but it’s oft-overlooked. In fact, the original version of the protocol docs I first read didn’t even mention it.

Every job submitted to gearman, whether background or foreground, accepts two

things. One is called “arguments” or “payload”, and that’s fed to the worker

in all JOB_ASSIGN* packets.

The other is a “unique ID”. This is the magic that gets ignored. In most libraries, if you don’t pass a unique ID for your request, the library will just generate a UUID for you.

Most libraries include no explanation as to why this is there, and it’s often

invisible to users. There’s a clue in the original implementation though.

You’ll note that the unique ID is not included in the original JOB_ASSIGN

packet sent to workers. That’s because this was always meant to be information

for the gearman service. Only later did they realize that many jobs were just

submitting the same unique ID as the payload, and added in the GRAB_JOB_UNIQ

and JOB_ASSIGN_UNIQ versions.

But generally you should have an ID. It’s not always a record ID, but it’s generally going to be “whatever you’d use to access cache entries”. It’s a unique string for this work. Sure, sometimes you have something obvious, like “account ID”, or sometimes you have free-form arguments, like a list of search terms. Whatever it is, you need to send this to the gearman server. You also should be hashing the unique ID, and choosing a gearman server to send to based on that hash, just like memcache clients do for cache keys. There’s a very good reason for this that we’ll get to later, but the most important thing is that you send a real, useful unique ID for every job you send to the server.

See, when your request arrives in a well-behaved gearman server (some don’t do

this properly), it will first look to see if is already aware of this ID. If

your job has asked for an ID that already exists, gearman will feed back the

same job handle that’s already in the queue to the client. For foreground jobs,

gearmand will multiplex the WORK_* packets that comes back from the worker

to all submitters. It’s like a distributed thread join.

This means that you have a guarantee that the number of concurrent active work units is deterministic.

n_active = min(n_uniques * n_gearman_servers, n_workers)

And actually, it’s better than that. If you followed the earlier advice to make your gearman client hash uniques and send submissions to the proper gearman server based on a hash, it’s just:

n_active = min(n_uniques, n_workers)

This means you can go look at your functions, and calculate the exact theoretical maximum load your backend resources will experience, and unbound auto-scaling for your workers to the exact capability of your backend. The math for capacity planning on those resources gets a lot simpler when you know the upper bounds of any of the variables deterministically. You can even dig through your cache hit/miss logs and find a good over-subscription scheme to adopt, and this calculus is much simpler when one of the variables is fixed.

Any old message queue can do the async work, but I haven’t seen any that can do a distributed thread join like gearman does.

This magic hasn’t lost value because of the sands of time. We are still writing

apps that need to scale reads, even if we’re sharding our databases. In fact,

response time requirements have gotten more extreme, not less. Being able to

build backends that respond rapidly and are scaled to meet exact demand

efficiently is critical in building scalable, responsive APIs. Gearman has

other tricks to help with user-interaction too, such as the WORK_STATUS

packets, which will send back numerator/denominators, or WORK_DATA, so you

can send partial responses while the final result is calculated, which is

perfect for sending a stale cache entry back immediately, but then updating

with the final and sending it with a WORK_COMPLETE.

Unfortunately, one reason this was lost is that when the Perl gearman client

was rewritten in C, hashing unique to pick a server for SUBMIT_JOB* packets,

was lost. And if you look, all of the language client libraries written since

have failed to do it, as most are just either using libgearman, or copying it.

I include the recent rustygear library I wrote in this equation. It’s not easy,

but it is such an awesome thing that it’s worth doing. I hope to find some time

to add this into rustygear, and maybe even with time, replace libgearman with

rustygear so other languages can use it.

Another reason I think that Gearman has lost momentum is that HTTP has gotten a lot smarter. You don’t need a special TCP protocol to achieve the level of responsiveness required to get this job done. I’ll be looking into a way to make the Gearman protocol ride on HTTP/2 and Websocket, so that folks can write workers and clients without needing a native gearman library.

I hope you see a solution to your problems in this, even if it’s not deploying gearmand and rewriting things as gearman workers. And if you think Gearman is the right solution for you, I’ll invite you to please join the gearman google group, and/or reach out to me and chat with us about that.

Happy Hacking